I was recently reading through some of my backlog of Dr. Dobb’s Journals (a PDF I receive monthly) and came across an article entitled The Requirements Payoff by Karl Wiegers. I’ve archived a copy of the PDF here and it can be found on pages 5-6.

I was recently reading through some of my backlog of Dr. Dobb’s Journals (a PDF I receive monthly) and came across an article entitled The Requirements Payoff by Karl Wiegers. I’ve archived a copy of the PDF here and it can be found on pages 5-6.

A lot of people seem to equate “requirements gathering” with “big design up front”, which is now often vilified as being antiquated and bloated. Nothing could be further from the truth (about requirements, not BDUF). In the book Agile Principles, Patterns, and Practices in C#, Uncle Bob talks about practicing Agile in a .Net world. In every one of his examples, you have to know what your requirements are ahead of time. The process goes as follows:

- Gather requirements

- Estimate requirements to determine length of project

- Work requirements in iterations

- Gauge velocity in coding requirements against estimate

- Determine whether your velocity requires you to either cut requirements or extend timelines

- Lather, rinse, repeat

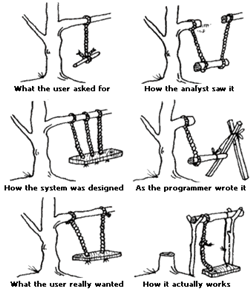

You see that the agile process doesn’t work without requirements. In the article, Wiegers says that according to a 1997 study, “Thirty percent or more of the total effort spent on most projects goes into rework, and requirement errors can consume 70% to 85% of all project rework costs”. That is a big penalty to pay for laziness or ineptitude in early requirements gathering. This doesn’t mean that the requirements collected at the beginning are rigid and inflexible. They are just a starting point. However, changing the requirements changes the estimate and also the expected cost in time and resources and can fall under the statistic quoted above.

Requirements are essential to TDD and BDD advocates, as well. The requirements are what a vast majority of the tests are written against. For instance, if the requirement is that the user name is an email address then a programmer will likely write a test (both positive and negative) verifying that the program behaves as expected when presented with an email address or a non-email address, etc. Without that requirement, a test might only be written to ensure the user name wasn’t blank and the stake-holders might be upset when the program behaves differently than they imagined in their heads (and you failed to ferret out in requirements gathering).

It is true that gathering proper requirements in advance costs time. Wiegers sums it up best, however, when he says, “These practices aren’t free, but they’re cheaper than waiting until the end of a project or iteration, and then fixing all the problems. The case for solid requirements practices is an economic one. With requirements, it’s not ‘You can pay me now, or you can pay me later.’ Instead, it’s ‘You can pay me now, or you can pay me a whole lot more later.'”